High above the altar of Immaculate Conception Church in Celina, Ohio, is a mural of the Blessed Mother being assumed into heaven. Crowds of people below watch with wonder: bishops, kings, priests, nuns, soldiers, working people, children. Even the pope is there, in the front row of reverence, as Mary is lifted into heaven along with a chorus of angels.

Far to the right in that mural, where people are not likely to notice it, is a stone marker with the name Vittur and the year 1902. That’s the signature of Joseph Vittur, who painted the mural and many works in churches across the Midwest, including at St. Augustine in Minster, Ohio, which like Immaculate Conception has been a Precious Blood parish since its inception.

In October, both IC and St. Augustine hosted a visitor, Janet Volk, Vittur’s great-granddaughter. Volk, who lives in Chicago, was touring churches in Ohio (including St. Joseph in Tiffin, Ohio) to see his work.

Vittur was born in 1853 in the village of San Cassiano, in South Tyrol, in what is now northern Italy but then was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. “There was an artistic heritage in that area, a tradition of artisan work: painting, carving, sculpting,” Volk said. Her great-grandfather showed talent, so he was sent to Vienna (possibly the Vienna Academy of Arts) to study art.

Vittur met his wife, Volk’s great-grandmother, Franziska Sim, in Vienna. He began to paint for a living but to earn additional money for his growing family, he agreed to act as a sales agent for a new type of bullet that a friend of his had invented. That drew unwanted attention from the French government, and Vittur decided to emigrate to the United States. His family followed later.

He was aboard the La Touraine when it departed for America in 1893. During the crossing, Volk says, he met Fr. Paulinus Trost, C.PP.S., a priest and painter who had studied art in Munich. They became friends and Fr. Trost gave him a letter of introduction that helped him find work in Chicago at several churches including Notre Dame de Chicago where his painting of biblical scenes fills the 2000-square foot dome.

Throughout her childhood, Volk had grown up hearing stories about Vittur. “I always knew I had a great-grandfather who was an artist,” she said. “The legend was that he painted on a scaffolding, like Michelangelo. I always thought that was a nice story family legend. It turns out to be true.”

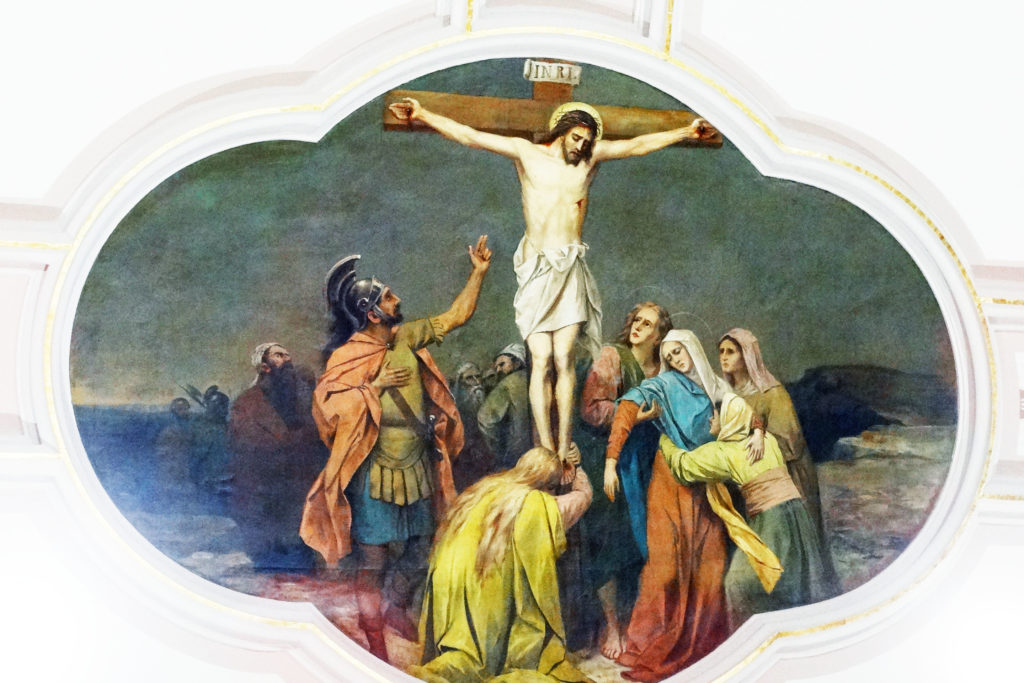

Vittur became one of the most recognized “copyist artists” of his era, according to Fr. David Hoying, C.PP.S., the province’s archivist and a son of St. Augustine Parish, where he grew up looking at Vittur’s paintings on the ceiling that depict the life of Christ. “A copyist painter is one who does not compose his own paintings, but uses subjects from other artists, either in whole, in part, or in combination,” he said. “Fr. Trost was also a copyist painter, for the most part.”

Fr. Hoying noted that “in our minds we may think of a copyist painter as someone who is second-rate or a fake. But to be a good copyist, an artist had to know what he was doing. At the time, it was a very legitimate endeavor, for it allowed churches to have first-rate artistic works at a lower cost.”

Vittur was a man of many talents, said Volk. He was an artist but also had a gift for language. Ladin, a Romance language not to be confused with Latin, was the language of his birth, but he could also speak Italian, French and German. “He was a great promoter,” Volk said. “If he was painting in a French church, he spoke French. In a German church, he spoke German.”

At IC, it is believed that Vittur may also be the artist who painted scenes of the Sermon on the Mount and the Wedding at Canna on the side walls of the church, but as Volk looked at them, she wasn’t so sure. To her, they don’t look like her great-grandfather’s work. Fr. Ken Schnipke, C.PP.S, IC’s pastor, said that at some point in the parish’s history, many historic documents were discarded so the parish can only guess at the provenance of those paintings.

At St. Augustine, the historic church, dedicated in 1849, was undergoing a major renovation in 1900–01 when Vittur was hired to beautify the formerly flat ceiling. “It was during this renovation that the original flat ceiling became the distinctive half-barrel ceiling, adorned with seven beautiful paintings, by the hand of Joseph Vittur, a copyist painter,” according to the parish’s website (staugie.com).

Fr. Hoying noted that when St. Augustine underwent renovations in the late 1950s, Fr. Bill Meyer, C.PP.S., the pastor at the time, wanted to remove Vittur’s paintings from the church’s ceiling. “However, the architect/designer strongly objected to that,” Fr. Hoying said. “He said that in themselves they were exceptional works of art that should not be destroyed.”

Seeing the works in person was a pilgrimage for Volk, a retired Lutheran pastor. “I think a lot about his life story: how courageous he was to start over in a new country, and how he used the gifts that God had given him so well,” she said. She likes to reflect on this even though Joseph Vittur’s life ended sadly; he suffered a nervous breakdown and died in an asylum at the age of 51. As a pastor, of course, Volk has seen the cycle of life roll from triumph to disaster, from joy to sorrow and back again, throughout her years of ministry.

Vittur’s work has long outlived him, which is what any artist would wish. All those figures from Scripture, the great and the small of humankind, look down upon the worshipers at Immaculate Conception, at St. Augustine, St. Joseph in Tiffin, at Notre Dame de Chicago. They gaze with the eyes that Joseph Vittur gave them, and which God, in turn, gave to Joseph Vittur.